Swap in recycled content, drop GWP fast

Quick wins often hide in plain sight. For many construction materials, increasing recycled content can slash cradle‑to‑gate global warming potential without touching the mix deign or compromising performance. The trick is knowing where it really works, what numbers to expect, and how to document it cleanly in an EPD so specifiers can act on it.

First, a reality check

The hunch that virgin inputs sometimes beat recycled on carbon rarely holds for core building materials. Metals and flat glass typically show large GWP cuts when recycled content goes up. There are edge cases in polymers and paper where benefits narrow due to energy mix or allocation rules, but consistent, recent data showing virgin beating recycled for construction mainstays is scarce. When numbers are missing, call it out rather than guess.

Where the swap works with little to no reformulation

Think like a chef who changes the origin of the flour, not the recipe. In practice that means specifying the same alloy, grade, or standard product, but sourcing from a supply route rich in post‑consumer or pre‑consumer scrap. Your production instructions, QA plans, and product datasheets usually stay the same, yet the A1–A3 line in your EPD moves sharply.

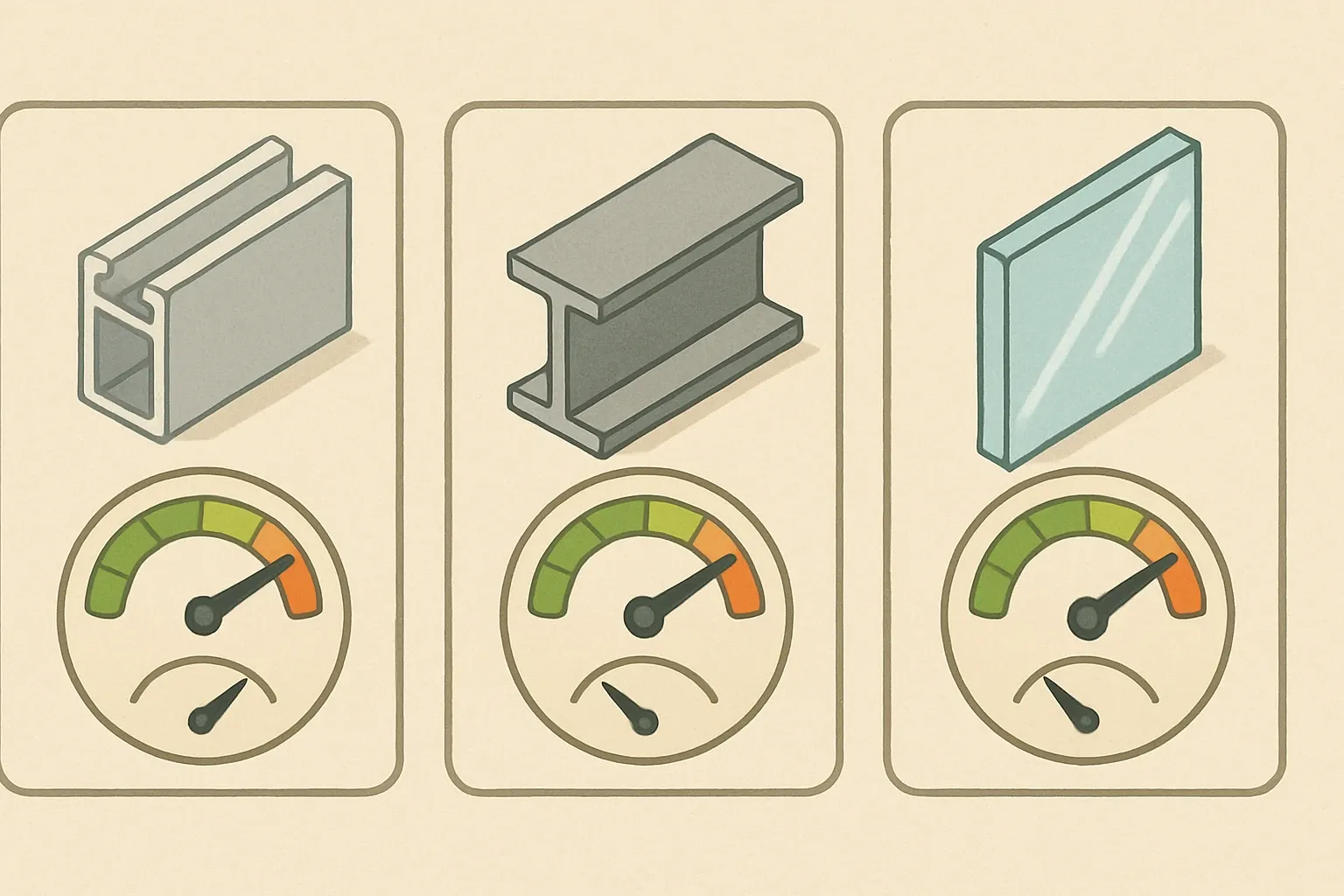

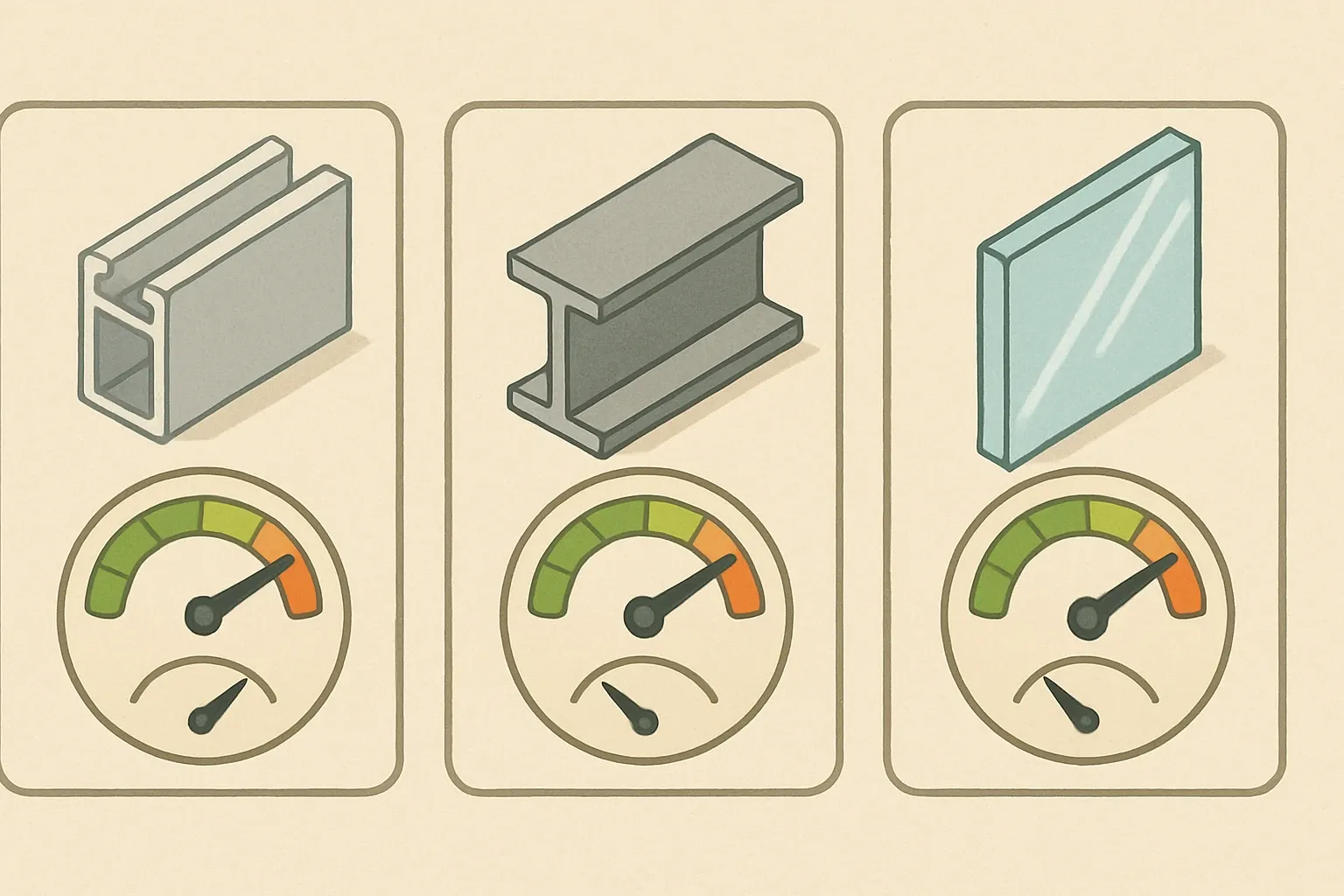

Aluminum: massive delta for the same alloy

Primary aluminum carries a heavy footprint largely from electricity used in smelting. Recent industry data puts global primary at about 15.1 t CO2e per tonne from mine to cast house, while producing recycled aluminum in the remelt stage is roughly 0.52 t CO2e per tonne. That is about a 95% savings, with even regional figures above 90% in North America (International Aluminium Institute, 2024) (IAI, 2024). For extrusions and plate, switching billet spec toward high post‑consumer content can deliver double‑digit percentage drops in your EPD GWP without changing alloy designation or temper.

Steel: choose the scrap route when available

Worldsteel’s latest indicator set shows a stark spread in 2024 average intensities. BF‑BOF sits around 2.34 t CO2e per tonne, scrap‑based EAF around 0.69, and DRI‑EAF near 1.47, all scope‑expanded to be comparable (worldsteel, 2025) (worldsteel, 2025). For rebar, hollow structural sections, and many plate or sheet specifications, preferring EAF‑route supply with high scrap automatically lowers A1–A3. The product meets the same ASTM or EN standard, your weld procedures do not change, yet your EPD moves into far stronger territory.

Want to slash carbon and win more specs?

Follow us on LinkedIn for insights on leveraging recycled content in your EPDs to unlock new business opportunities.

Float glass: cullet is quiet carbon

Raising cullet content reduces both fuel use and calcination emissions. AGC’s low‑carbon float glass EPD, published in INIES, reports 5.5 kg CO2e per m² for 4 mm glass with recycled content above 50%, a marked drop versus standard float produced in the same plants (AGC, 2024) (AGC, 2024). Industry process data remains consistent that about a 10% cullet increase cuts furnace CO2 roughly 5% and energy about 2.5% depending on furnace design and fuel mix (Verallia, 2024).

When recycled does not help much

Two patterns can blunt the benefit. First, energy intensity and grid mix. Mechanically recycled polymers processed on coal‑heavy grids can show modest gains, sometimes negligible, compared with efficient virgin production. Second, allocation and system boundary choices in the governing PCR can reassign burdens in unexpected ways for some fiber and polymer feedstocks. If you cannot find recent, program‑operator‑verified numbers that show a clear advantage, say so in the EPD narrative and keep collecting primary data.

EPD playbook for easy substitutions

You do not need to revamp formulations to earn lower numbers. You do need supplier proof and clean modeling.

- Ask mills, smelters, and float lines for plant‑specific EPDs and recycled content attestations aligned to your reference year.

- Record route of production for metals and cullet ratio for glass at the plant level, not corporate averages.

- Model A1–A3 with those verified inputs, then lock in QA so purchasing keeps buying to that spec.

Commercial upside

Specifiers increasingly filter by a simple threshold, often the best performing quintile within a product category. Hitting that bracket with the same product code and datasheet shortens sales cycles and protects price. The cost to change a supply route is usually small compared with revenue unlocked when your product no longer triggers a carbon penalty in bid scoring.

What to do this quarter

Prioritize three SKUs where supply‑route swaps are realistic. Aluminum profiles to high‑PCR billet. Steel rebar to confirmed scrap‑EAF. Architectural glass to lines with higher cullet ratios. Update purchasing specs, collect attestations, refresh the EPDs, and put the new GWP numbers in your submittals. It is a tidy lift that reads as real climate action and real spec advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does using high recycled content aluminum really change an EPD if the alloy stays the same?

Yes. Primary aluminum averages about 15.1 t CO2e per tonne while recycled remelt is about 0.52 t CO2e per tonne, a ~95% reduction that flows directly into A1–A3 in your EPD when you switch billet supply to higher post‑consumer content (IAI, 2024).

For steel, how big is the emissions gap between BOF and scrap‑EAF routes?

Worldsteel’s 2024 intensities show about 2.34 t CO2e per tonne for BF‑BOF and 0.69 for scrap‑EAF using the expanded indicator. That gap is often the single largest lever available without changing grades or dimensions (worldsteel, 2025).

Will higher cullet content in float glass affect optical quality or performance?

Not when managed at the plant with proper sorting and furnace control. Recent EPDs show lower GWP at higher cullet shares while maintaining standard performance, for example 5.5 kg CO2e per m² at 4 mm for AGC low‑carbon float glass published in INIES (AGC, 2024).